Games are teaching tools. A way to learn how to navigate a situation, while having greatly reduced prizes and punishments. Losing cops and robbers doesn’t have as much prison time as being an actual robber.

So what does a game teach you? Fundamentally, how to play the game. Through play you learn what skills you need to be good at it.

While a good game will have lots of opportunities to develop your in-game skills, a great game will teach you things applicable outside of the game. Cops and robbers teaches us: if you’re going to commit a crime, don’t get caught.

As children, most of the games we play are push your luck games with our parents, because we don’t yet know our boundaries. The game of how much can I get away with will stay with us long after we’re children. Later re-editions include how high can I turn up the volume and how fast can I drive. In the real world, games are all about learning exactly how much straw breaks a camels back, long before we own a camel.

For more on everyday scenarios as games, see Games People Play

Go, the oldest game that people still play.

Go feels more like it was discovered then invented. It’s beautiful in its simplicity, while being incalculably complex. The core of the game can be taught in a single sentence, but the strategy hasn’t stopped developing since its creation. Here is where Go teaches life lessons in spades.

Let me walk you through playing, just a little.

Players take turns placing black and white colored stones in a grid, with the goal of having your colored stones surround the most empty spaces by the time the game is over, which is when both players choose to pass. If you completely surround all the edges of an opponents stone(s) you remove them from the board and they count as extra point(s) for you.

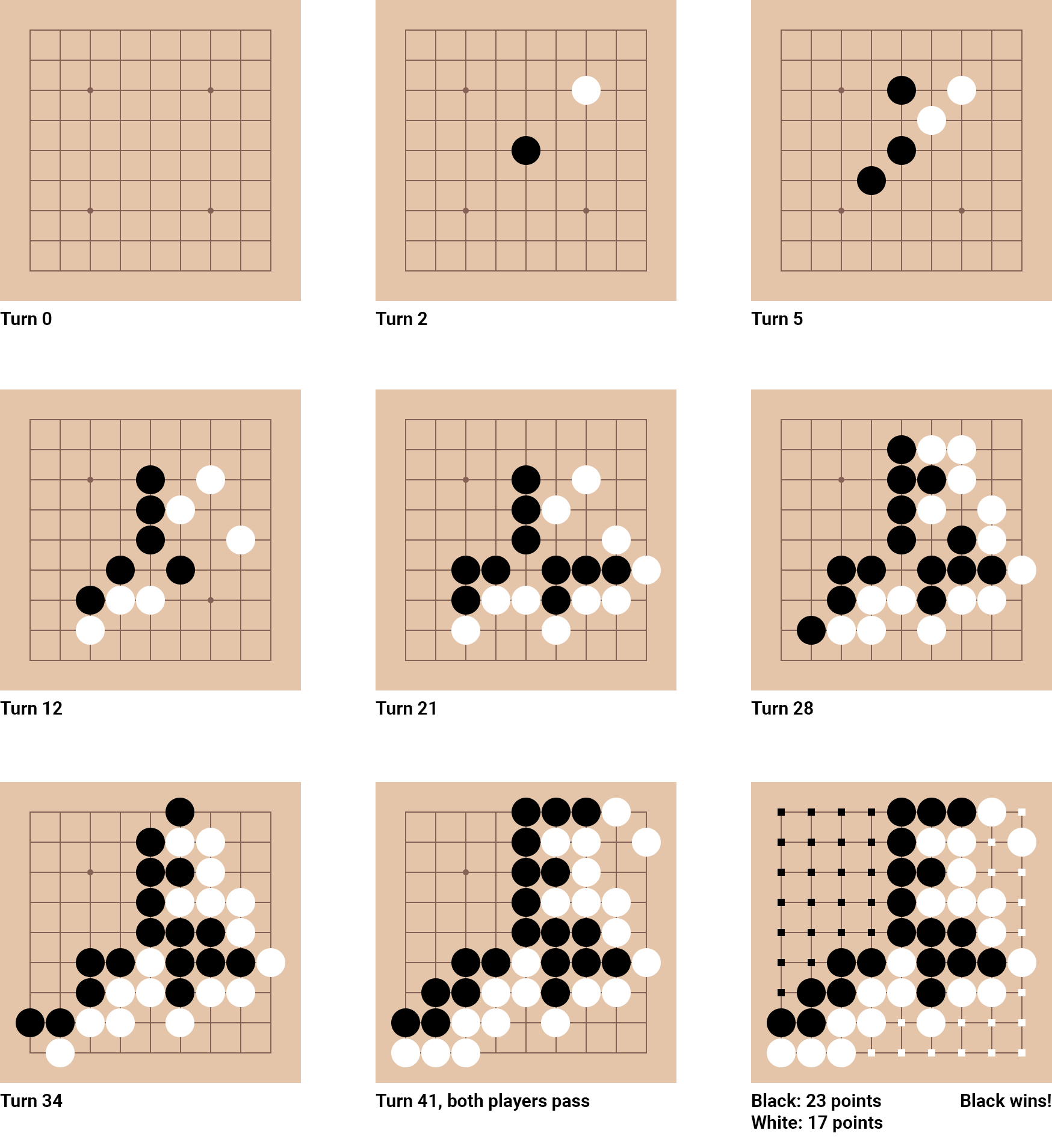

Here are some snapshots from how a small game could play out:

Beautiful. It’s like watching the growth of bacteria or crystals, the shapes feel so natural. It’s no wonder that Go appeals so much to monks and mathematicians.

Now, though other games can teach you life lessons, I’ve found that because of the simplicity of Go, it lends itself to being interpreted through countless metaphors, so you’re more likely to interpret the game in a way which strikes a chord with you. The following list is by no means complete, but these are the chords of mine it has struck.

Lesson 1: When you don’t know what you want, be flexible. When you do know what you want, be strong.

Strength and flexibility are two sides of the same coin. Don’t put all your eggs in one basket is a phrase which touches on this, though lacks the full picture.

In Go, you can treat stones like contracts; a stone you placed on the board is saying I could earn you points over here. Playing stones all around the board makes a lot of claims to various territories, but over time you’ll find only some of those pay off. Whereas placing stones in the same area strengthen each other by becoming harder to surround or split apart, and keep good on that contract.

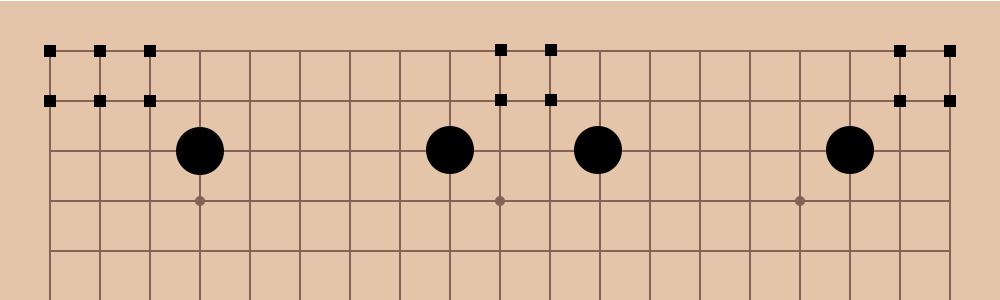

Below, black makes a claim to the square dots of territory using these stones, hoping to win these points. But guess what, there’s another player whose job it is to disagree with them.

In the real world, this means when you are uncertain what you want, try lots of things, and when you know what you want, double down on it. To extend the metaphor; don’t put all your eggs in one basket, until you know it’s made of steel, then go nuts.

Lesson 2: Be ready to lose the thing you want least.

Inevitably some of those “contracts” just don’t come through, and that’s because something else was more important. The price to pay for the things you want, are the things you want less.

Let’s say you did diversify, and spent a little time trying a range of things. When it comes time to double down, nobody has a grip strong enough to hold onto everything. If you try, you’re going to do a bad job maintaining a grasp on things that are important. So be ready to give up things you have when something more valuable comes along, so you can give it the attention it needs.

On the flipside, if you never invested in anything, you have nothing to lose.

Lesson 3: Don’t make a decision until you have to.

If you have options, opportunity lies everywhere, but picking one direction will result in others becoming unavailable. This is a part of path dependency, where the events that can happen in the future rely on events that have come before.

If you decide earlier than you need to, you will lose the chance to change your mind in the period before all options become unavailable.

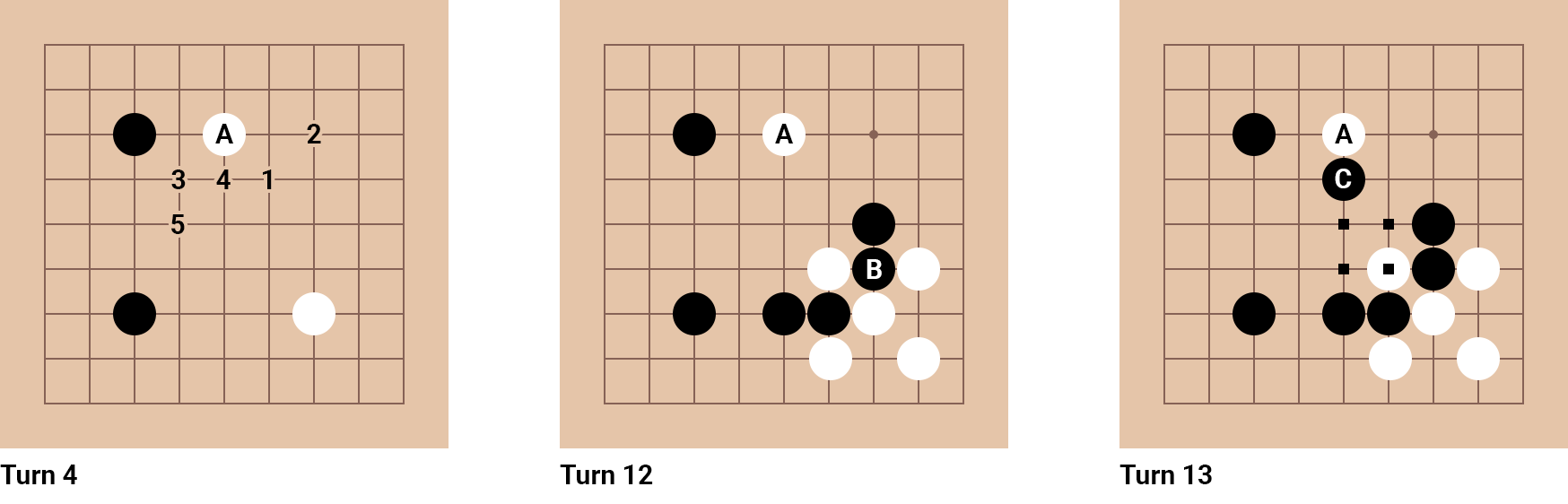

In the example below, white has played the stone at A, threatening to take a large territory on the top right side, and you have a number of choices to deal with it directly (numbered 1 to 5). However, making a decision now will have major repercussions for the rest of the board, and more importantly, it isn’t urgent. So instead, black plays elsewhere and thinks about claiming territory at B. The outcome of the little fight over territory leads to a situation where a stone placed at C would help score black 4 points in the center and directly put pressure on A.

Should the decision to react to A have been made earlier, the opportunity to score those points may not have been there.

So the next time someone asks you “do you want x?”, and you’re not sure, ask them “how soon do I need to decide?”

Thanks for reading! If you play go and want a game, challenge me!

If you like my words, subscribe get more posts.

Or, if you wanna get in touch, email me sam@sunlightafterdark.com

Disclaimer for Go players: I’m only a 12kyu, please forgive my bad examples.